THE TORNADO

At 3:08 on March 23, 1917 ugly greenish black clouds and tornado winds dropped into the city from over the Knobs.

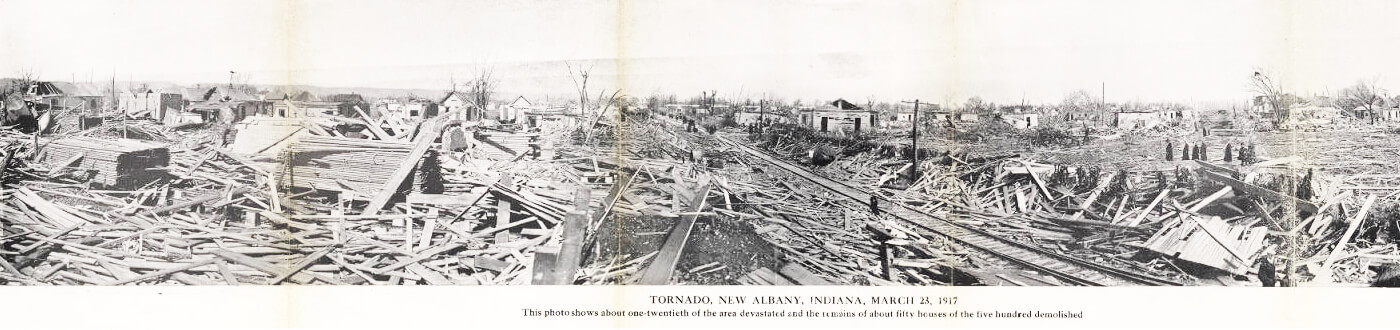

Within seconds, hundreds of homes were reduced to wreckage.

“Where peaceful, happy homes were and merry children played in carefree glee and where industry was wont to ply its busy wheels, today all is death and destruction and silence.” So reported the New Albany Ledger on March 24, 1917, the day after the tornado struck the city. “Today,” the Ledger continued, “New Albany is plunged in mourning for its dead, prayers for its injured, and compassion for its suffering.”The West Union neighborhood had been the first area of the city hit by the swirling winds. Cherry, Ealy, State and Pearl Streets were a jumble of twisted wreckage. At the Oldham School rescue workers brought out one by one the bodies of youngsters who had been in class when the wind had suddenly transformed the building into a heap of bricks. On Ealy Street eleven bodies were found in the rubble of four adjoining houses.

From West Union the wind had jumped to the Kahler woodworking plant at the junction of Grantline and Charlestown Roads. The plant was flattened and a day later a desk from the factory was found twenty-five miles up the Ohio River on the Kentucky side, with its contents intact. The Rasmussen greenhouses on Vincennes Street were almost totally destroyed. The wind whirled along Charlestown Road leveling everything in its path. The huge DePauw mansion was wrecked and twenty-six homes in one block near South Street were wiped out. Then the tornado lifted and vanished into the northeast. It had crossed New Albany in a matter of minutes, leaving bodies, scores of persons trapped in wreckage, 3,000 homeless and property damage estimated at two million dollars. So sudden had been the wind that downtown New Albany was completely unaware of the catastrophe until distraught survivors rushed down State Street with the news. The city’s fire and police departments, aided by private citizens, organized rescue operations immediately, but were hampered by driving rain which followed the wind. Help was dispatched from Jeffersonville and Louisville and crews worked desperately through the night to pull the injured from the wreckage. They worked by flaring kerosene torches since all street lights in the city had been put out of operation by the storm. At St. Edwards Hospital, doctors and nurses worked through a sleepless night to administer emergency care to the casualties who overflowed into corridors after every room was filled. At the city’s funeral homes a grimmer scene was enacted as still, white-sheeted bodies were placed row on row.

Mayor Robert W. Morris issued a call for formation of a citizens’ relief committee and help came from other sources, too. The Red Cross soon had seventy trained workers in New Albany; Indiana National Guardsmen, still tanned from Mexican border service against the bandit army of Pancho Villa, patrolled the devastated area; Louisville contributed $20,000 to the relief fund, and $10,000 came from St. Louis. Other cities and organizations from all parts of the nation offered aid.

Many of the homeless were taken in by their more fortunate fellow citizens, but others attempted to return to their ruined dwelling until the rain and cold compelled them to seek shelter elsewhere. Trusted inmates of the Jeffersonville Reformatory did yeoman service in clean-up operations and other Reformatory prisoners took up a voluntary collection among themselves to help the tornado victims.

Gradually, through its own efforts and generous aid from the outside, the city returned to normal. Rebuilding operations were spurred by New Albany banks which pooled their resources to make $100,000 available in long-term low-interest loans to those whose businesses and homes had been damaged or destroyed. Before long, all traces of destruction had vanished and the tornado became only a topic for reminiscence.

But one monument remains today from that catastrophe. As an aftermath of the tornado the New Albany Chapter of the American Red Cross was organized and observes this year its 40th anniversary – an agency for good born from a tornado that ranks among the most disastrous in American history.

Story Courtesy - NA-FC Library / Floyd County Historical Society

Image - Indiana Historical Society